Flower Power!

Fall 2024 - Spring 2025

For my year-long Senior Capstone Team Design project, I worked on a Hybrid Concentrator Photovoltaic/Thermal “Sunflower Receiver” (*try saying that five times fast*). This project was part of the Escarra Research Group led by Professor Matthew Escarra, and was initially funded by DOE’s ARPA-E and in partnership with the University of San Diego, San Diego State University, Boeing-Spectrolab, and Otherlab. I led the second Capstone team for this project, as there was a first Capstone team in the Fall 2023-Spring 2024 academic year that initially built the system on the roof of Flower Hall at Tulane University (there is a third team working on the project for the Fall 2025-Spring 2026 academic year!). My team mainly focused on improving the system based on the work that the first team did, so when my team started, we were on the third iteration of the sunflower receiver (SFR3).

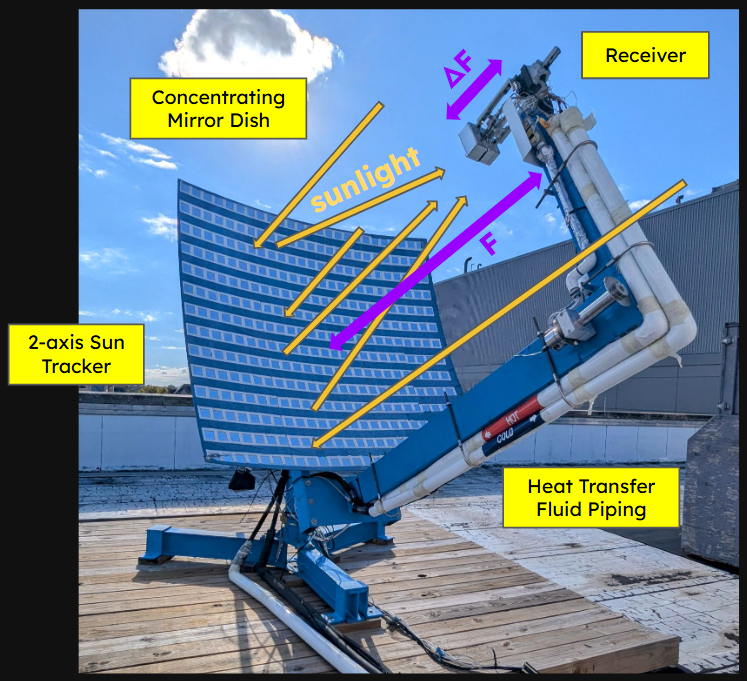

The Sunflower Receiver consists of a parabolic mirror that concentrates sunlight onto a receiver, which is mounted on an arm that extends from a support frame. The receiver module contains an array of photovoltaic (PV) solar cells, a cooling block, and a cooling coil. The solar cells are mounted on top of the cooling block, and the cooling coil is connected to the outlet of the cooling block and winds around the module. The cooling block contains channels for water to flow through, with inlet and exit holes on the back of the block. The whole system is mounted on a 2-axis tracker that can rotate azimuthally and tilt vertically to always be pointing towards the sun. The ratio of electrical vs. thermal energy produced by the system can be adjusted by changing the distance of the PV array from the focal point (F), as illustrated in the image below. When the PV array is directly on the focal plane, more electrical energy is produced because almost all the sunlight is hitting the solar cells, but when the PV array is in front of the focal plane, more thermal energy is produced since more stray light is hitting the cooling coil instead of the array.

The system operates by pumping cold water from Flower Hall (or whichever building the system is integrated with) to the inlet of the cooling block, where the water flows through the channels and transfer’s heat from the solar cells to the water, thus cooling the cells and heating the water simultaneously. The hot water exits the cooling block and heats up more as it flows through the cooling coil before it is pumped back to the building. The thermal energy from the hot water is collected via a heat exchanger while the PV array independently generates electrical energy. This system provides both thermal and electrical energy for the building with superior efficiencies and a lower footprint compared to a conventional solar panel. Below is a VERY simplified diagram of the system which includes the Building Loop (the one I just described) and the Test Loop (for non-building testing).

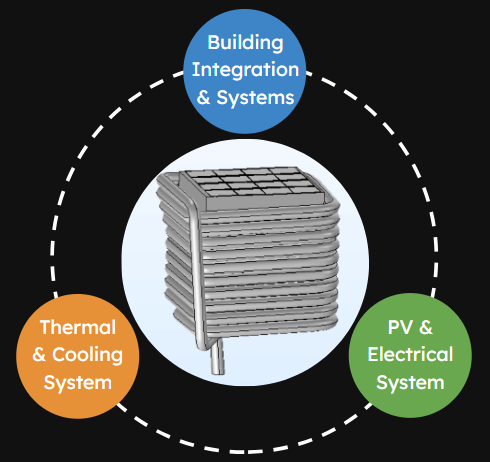

Since this was quite an intensive project, we broke it up into three main areas that my teammates and I would be responsible for: systems engineering and building integration, the photovoltaics/electrical system, and the thermal/cooling system. Since my strengths lie in holistic design, big-picture thinking, and management/organization, I took on the systems engineering and building integration and was the team leader. My role basically covered everything besides the receiver module, although I worked with a little bit of everything since the thermal and electrical system were all interconnected with the system in some capacity. Throughout my time with the project, my job as a Fabrication Technician at Tulane’s MakerSpace proved invaluable, as I used many of the MakerSpace tools, machines, and my general handiness to construct/install many of the things pictured below.

Many grueling hours were spent on the roof of Flower Hall installing piping insulation, PVC covers, thermocouples, filters, and installing/removing the receiver module (many-a-times), but now I can proudly say that I am very confident in my piping installation abilities, enough to fix the plumbing in my house in the future (yay!). I also spent many hours in our lab calibrating the mass flow sensor, dissecting a broken cooling coil to diagnose the cause of failure, performing flow and clog tests on the cooling coil and block, troubleshooting a broken datalogger, assembling the receiver module, and so much more. As you can tell, it was quite an eventful year of learning.

Going into this project, I knew it would be challenging and time-consuming given its complexity and Professor Escarra’s high expectations, however that didn’t discourage me. I wanted to take on something that would push me to learn and grow, and my entrepreneurial side was excited by the possibility that this project could one day make it to market. Even after I graduated and started working on my +1 master’s degree, I still happily involved myself as a mentor to the next team, attending all of their weekly meetings and giving advice wherever I could. Luckily, the next team had five team members instead of three, so they were more equipped to handle the time-consuming nature of the project. Having only three team members was quite rough, sometimes causing me to spend 15-20 hours per week on the project, working out kinks and constantly testing, troubleshooting, and doing hands-on work on the roof, in the MakerSpace, and in the lab. Nonetheless, this project was crucial in helping me grow my management and leadership skills, and if I went back in time, I would still choose it because of how much it challenged me and helped me grow.